Dassault Mirage III

| Mirage III | |

|---|---|

|

|

|

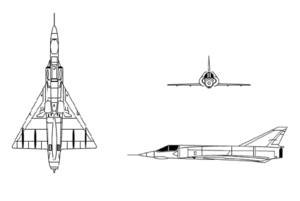

| Royal Australian Air Force Mirage IIIO(F) (fighter) from 2 Operational Conversion Unit. | |

| Role | Interceptor aircraft |

| Manufacturer | Dassault Aviation |

| First flight | 17 November 1956 |

| Introduced | 1961 |

| Status | Active service |

| Primary users | French Air Force Pakistan Air Force |

| Number built | 1,422 |

| Variants | Dassault Mirage IIIV Dassault Mirage 5 Atlas Cheetah |

The Mirage III is a supersonic fighter aircraft designed in France by Dassault Aviation during the late 1950s, and manufactured both in France and a number of other countries. It was a successful fighter aircraft, being sold to many air forces around the world and remaining in production for over a decade. Some of the world's smaller air forces still fly Mirage IIIs or variants as front-line equipment today.

Contents |

Development

The Mirage III family grew out of French government studies begun in 1952 that led in early 1953 to a specification for a lightweight, all-weather interceptor capable of climbing to 18,000 m (59,040 ft) in six minutes and able to reach Mach 1.3 in level flight.

Dassault's response to the specification was the Mystère-Delta 550, a diminutive and sleek jet that was to be powered by twin Armstrong Siddeley MD30R Viper afterburning turbojets, each with thrust of 9.61 kN (2,160 lbf). A SEPR liquid-fuel rocket motor was to provide additional burst thrust of 14.7 kN (3,300 lbf). The aircraft had a tailless delta configuration, with a 5% chord (ratio of airfoil thickness to length) and 60 degree sweep.

The tailless delta configuration has a number of limitations. The lack of a horizontal stabilizer meant flaps cannot be used, resulting in a long takeoff run and a high landing speed. The delta wing itself limits maneuverability; and suffers from buffeting at low altitude, due to the large wing area and resulting low wing loading. However, the delta is a simple and pleasing design, easily built and robust, capable of high speed in a straight line, and with plenty of space in the wing for fuel storage.

The first prototype of the Mystere-Delta, without afterburning engine or rocket motor and with an unusually large vertical stabiliser, flew on 25 June 1955. After some redesign, reduction of the fin to more rational size, installation of afterburners and rocket motor, and renaming to Mirage I, in late 1955, the prototype attained Mach 1.3 in level flight without rocket assist, and Mach 1.6 with the rocket.

However, the small size of the Mirage I restricted its armament to a single air-to-air missile, and even before this time it had been prudently decided the aircraft was simply too tiny to carry a useful warload. After trials, the Mirage I prototype was eventually scrapped.

Dassault then considered a somewhat bigger version, the Mirage II, with a pair of Turbomeca Gabizo turbojets, but no aircraft of this configuration was ever built. The Mirage II was bypassed for a much more ambitious design that was 30% heavier than the Mirage I and was powered by the new SNECMA Atar afterburning turbojet with thrust of 43.2 kN (9,700 lbf). The Atar was an axial flow turbojet, derived from the German World War II BMW 003 design.

The new fighter design was named the Mirage III. It incorporated the new area ruling concept, where changes to the cross section of an aircraft were made as gradual as possible, resulting in the famous "wasp waist" configuration of many supersonic fighters. Like the Mirage I, the Mirage III had provision for a SEPR rocket engine.

The prototype Mirage III flew on 17 November 1956, and attained a speed of Mach 1.52 on its seventh flight. The prototype was then fitted with the SEPR rocket engine and with manually-operated intake half-cone shock diffusers, known as souris ("mice"), which were moved forward as speed increased to reduce inlet turbulence. The Mirage III attained a speed of Mach 1.8 in September 1957.

The success of the Mirage III prototype resulted in an order for 10 pre-production Mirage IIIAs. These were almost two meters longer than the Mirage III prototype, had a wing with 17.3% more area, a chord reduced to 4.5%, and an Atar 09B turbojet with afterburning thrust of 58.9 kN (13,230 lbf). The SEPR rocket engine was retained, and the aircraft were fitted with Thomson-CSF Cyrano Ibis air intercept radar, operational avionics, and a drag chute to shorten landing roll.

The first Mirage IIIA flew in May 1958, and eventually was clocked at Mach 2.2, making it the first European aircraft to exceed Mach 2 in level flight. The tenth IIIA was rolled out in December 1959. One was fitted with a Rolls-Royce Avon 67 engine with thrust of 71.1 kN (16,000 lbf) as a test model for Australian evaluation, with the name "Mirage IIIO". This variant flew in February 1961, but the Avon powerplant was not adopted.

Mirage IIIC and Mirage IIIB

The first major production model of the Mirage series, the Mirage IIIC, first flew in October 1960. The IIIC was largely similar to the IIIA, though a little under a half meter longer and brought up to full operational fit. The IIIC was a single-seat interceptor, with an Atar 09B turbojet engine, featuring an "eyelet" style variable exhaust.

The Mirage IIIC was armed with twin 30 mm DEFA revolver-type cannon, fitted in the belly with the gun ports under the air intake. Early Mirage IIIC production had three stores pylons, one under the fuselage and one under each wing, but another outboard pylon was quickly added to each wing, for a total of five. The outboard pylon was intended to carry a Sidewinder air-to-air missile (AAM), later replaced by Matra Magic.

Although provision for the rocket engine was retained, by this time the day of the high-altitude bomber seemed to be over, and the SEPR rocket engine was rarely or never fitted in practice. In the first place, it required removal of the aircraft's cannon, and in the second, apparently it had a reputation for setting the aircraft on fire. The space for the rocket engine was used for additional fuel, and the rocket nozzle was replaced by a ventral fin at first, and an airfield arresting assembly later.

A total of 95 Mirage IIICs were obtained by the AdA, with initial operational deliveries in July 1961. The Mirage IIIC remained in service with the AdA until 1988.

The French Armée de l'Air (AdA) also ordered a two-seat Mirage IIIB operational trainer, which first flew in October 1959. The fuselage was stretched about a meter (3 ft 3.5 in) and both cannons were removed to accommodate the second seat. The IIIB had no radar, and provision for the SEPR rocket was deleted, although it could carry external stores. The AdA ordered 63 Mirage IIIBs (including the prototype), including five Mirage IIIB-1 trials aircraft, ten Mirage IIIB-2(RV) inflight refueling trainers with dummy nose probes, used for training Mirage IVA bomber pilots, and 20 Mirage IIIBEs, with the engine and some other features of the multi-role Mirage IIIE. One Mirage IIIB was fitted with a fly-by-wire flight control system in the mid-1970s and redesignated Mirage IIIB-SV (Stabilité Variable); this aircraft was used as a testbed for the system in the later Mirage 2000.

Mirage IIIE

While the Mirage IIIC was being put into production, Dassault was also considering a multi-role/strike variant of the aircraft, which eventually materialized as the Mirage IIIE. The first of three prototypes flew on 1 April 1961.

The Mirage IIIE differed from the IIIC interceptor most obviously in having a 300 mm (11.8 in) forward fuselage extension to increase the size of the avionics bay behind the cockpit. The stretch also helped increase fuel capacity, as the Mirage IIIC had marginal range and improvements were needed. The stretch was small and hard to notice, but the clue is that the bottom edge of the canopy on a Mirage IIIE ends directly above the top lip of the air intake, while on the IIIC it ends visibly back of the lip.

Many Mirage IIIE variants were also fitted with a Marconi continuous-wave Doppler navigation radar radome on the bottom of the fuselage, under the cockpit. However, while no IIICs had this feature, it was not universal on all variants of the IIIE. A similar inconsistent variation in Mirage fighter versions was the presence or absence of an HF antenna that was fitted as a forward extension to the vertical tailplane. On some Mirages, the leading edge of the tailplane was a straight line, while on those with the HF antenna the leading edge had a sloping extension forward. The extension appears to have been generally standard on production Mirage IIIAs and Mirage IIICs, but only appeared in some of the export versions of the Mirage IIIE.

The IIIE featured Thomson-CSF Cyrano II dual mode air / ground radar; a radar warning receiver (RWR) system with the antennas mounted in the vertical tailplane; and an Atar 09C engine, with a petal-style variable exhaust.

The first production Mirage IIIE was delivered to the AdA in January 1964, and a total of 192 were eventually delivered to that service.

Total production of the Mirage IIIE, including exports, was substantially larger than that of the Mirage IIIC, including exports, totaling 523 aircraft. In the mid-1960s one Mirage IIIE was fitted with the improved SNECMA Atar 09K-6 turbojet for trials, and given the confusing designation of Mirage IIIC2.

Mirage IIIR

A number of reconnaissance variants were built under the general designation of Mirage IIIR. These aircraft had a Mirage IIIE airframe; Mirage IIIC avionics; a camera nose and unsurprisingly no radar; and retained the twin DEFA cannon and external stores capability. The camera nose accommodated up to five OMERA cameras.

The AdA obtained 50 production Mirage IIIRs, not including two prototypes. The Mirage IIIR preceded the Mirage IIIE in operational introduction. The AdA also obtained 20 improved Mirage IIIRD reconnaissance variants, essentially a Mirage IIIR with an extra panoramic camera in the most forward nose position, and the Doppler radar and other avionics from the Mirage IIIE.

Exports and license production

Exports

The largest export customers for Mirage IIICs built in France were Israel and South Africa as the Mirage IIICZ. Some export customers obtained the Mirage IIIB, with designations only changed to provide a country code. Such as the Mirage IIIDA for Argentina, Mirage IIIDBR and Mirage IIIDBR-2 for Brazil. Mirage IIIBJ for Israel, Mirage IIIDL for Lebanon, Mirage IIIDP for Pakistan, Mirage IIIBZ and Mirage IIIDZ and Mirage IIID2Z for South Africa, Mirage IIIDE for Spain and Mirage IIIDV for Venezuela.

After the outstanding Israeli success with the Mirage IIIC, scoring kills against Syrian Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-17s and MiG-21 aircraft and then achieving a formidable victory against Egypt, Jordan, and Syria in the Six-Day War of June 1967, the Mirage III's reputation was greatly enhanced. The "combat-proven" image and low cost made it a popular export success.

A good number of IIIEs were built for export as well, being purchased in small quantities by Argentina as the Mirage IIIEA and Mirage IIIEBR-2 Brazil as the Mirage IIIEBR, Lebanon as the Mirage IIIEL, Pakistan as the Mirage IIIEP, South Africa as the Mirage IIIEZ, Spain as the Mirage IIIEE, and Venezuela as the Mirage IIIEV, with a list of subvariant designations, with minor variations in equipment fit. Dassault believed the customer was always right, and was happy to accommodate changes in equipment fit as customer needs and budget required. Pakistani Mirage 5PA3, for example, were fitted with Thomson-CSF Agave radar with capability of guiding the Exocet anti-ship missile.

Some customers obtained the two-seat Mirage IIIBE under the general designation Mirage IIID, though the trainers were generally similar to the Mirage IIIBE except for minor changes in equipment fit. In some cases they were identical, since two surplus AdA Mirage IIIBEs were sold to Brazil under the designation Mirage IIIBBR, and three were similarly sold to Egypt under the designation Mirage 5SDD. New-build exports of this type included aircraft sold to Abu Dhabi, Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Egypt, Gabon, Libya, Pakistan, Peru, Spain, Venezuela, and Zaire.

Export versions of the Mirage IIIR were built for Pakistan as the Mirage IIIRP and South Africa as the Mirage IIIRZ, and Mirage IIIR2Z with an Atar 9K-50 jet engine. Export versions of the IIIR recce aircraft were purchased by Abu Dhabi, Belgium, Colombia, Egypt, Libya, Pakistan, and South Africa. Some export Mirage IIIRDs were fitted with British Vinten cameras, not OMERA cameras. Most of the Belgian aircraft were built locally.

Israel

The IDF/AF purchased three models of the Mirage III:

- 70 Mirage IIICJ single-seat fighters, received between April 1962 and July 1964.

- 2 Mirage IIIRJ single-seat photo-reconnaissance aircraft, received in March 1964.

- 4 Mirage IIIBJ two-seat combat trainers, three received in 1966 and one in 1968.

The Israeli AF Mirage III fleet went through several modifications during their service life.

Over the demilitarized zone on the Israeli side of the border with Syria, a total of 6 MIGs were shot down the first day Mirages fought the Migs. In the Six-Day war, except for 12 Mirages (4 in the air and 8 on the ground), left behind to guard Israel's from Arab bombers, all the Mirages were fitted with bombs, and sent to attack the Arab air bases. However the Mirage's performance as a bomber was limited. During the following days Mirages performed as fighters, and out of a total of 58 Arab planes shot down in air combat during the war, 48 were accounted for by Mirages.

In the 1973 (Yom Kipur war) the Mirage performed in air to air operations only.

Argentina

License production

The Mirage IIIE was also built under license in Australia, Belgium and Switzerland.

Australia

While an experimental Rolls-Royce Avon-powered version did not enter production, the Australian government decided that the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) would receive the IIIE, albeit a variant assembled by the Government Aircraft Factory (GAF) in Fishermans Bend, Melbourne from Australian-made components, under the designation Mirage IIIO. The major difference between the IIIE and the IIIO was the avionics installed. The other major Australian aircraft manufacturer at the time, the Commonwealth Aircraft Corporation (CAC), also in Melbourne, built the SNECMA Atar engine.

GAF produced two variants: the Mirage IIIO(F), which was an interceptor, and the Mirage IIIO(A), a surface attack aircraft. Dassault produced two sample IIIO(F) aircraft, with the first flying in March 1963. GAF completed 48 IIIO(F) and 50 IIIO(A) aircraft.

All the surviving Mirage IIIO(F) aircraft were converted to IIIO(A) standard between 1967 and 1979. The Mirage was finally withdrawn from RAAF service in 1988, and 50 surviving examples were sold to Pakistan in 1990.

Belgium

Switzerland

In 1961, Switzerland bought a single Mirage IIIC from France. This Mirage IIIC was used as development aircraft. The Swiss Mirages was built in Switzerland by F+W Emmen (today RUAG ) (the federal government aircraft factory in Emmen) as the Mirage IIIS. As did Australia, one French-made aircraft was bought in preparation for license construction. Cost overruns during the production led to the so-called"Mirage affair" . In all, 36 Mirage IIIS interceptors were built with strengthened wings, airframe, and undercarriage. The Swiss Air Force required performances comparable to those of carrier based planes. The airframes were reinforced so the aircraft could be moved by lifting them over other aircraft with a crane. The caverns in the mountains offer very little space to maneuver around parked aircraft. Also, the strengthened frames allowed for JATO assisted takeoffs. The Swiss Mirages are equipped with RWS, Chaff & Flair dispensers. Avionics differed as well, with the most prominent difference being that the Thomson-CSF Cyrano II radar was replaced by Hughes TARAN-18 system, giving the Mirage IIIS compatibility with the Hughes AIM-4 Falcon AAM. Also the Mirage IIIS had the wiring to carry a Swiss built nuclear bomb or French nuclear bomb. The Swiss nuclear bomb was stopped in the preproduction stage and Switzerland did not purchase the French made bomb. The Mirage IIIS had an Integral fuel tank under the aft belly, this fuel tank could be removed and a replaced with an adapter of the same shape. This adapter housed a SEPR-Rocket engine with its liquid fuel tanks. With the SEPR rocket, the Mirage IIIS easily reached altitudes of 20 000m. The rocket fuel was very hazardous and highly toxic, so the SEPR rocket was not used very often. The Mirage IIIRS could also carry a photo-reconnaissance centerline pod. And an Integral fuel tank under the aft belly it carried a smaller fuel load but allowed a back looking film camera to be added. In the early 1990s, the 30 surviving Swiss Mirage IIIS interceptors were put through an upgrade program, which included fitting them with fixed canards and updated avionics. The Mirage IIIS were phased out of service in 1999. The remaining Mirage IIIRS, BS and DS were taken out of service in 2003. [1]

Variants

- M.D.550 Mystere-Delta

- Single-seat delta-wing interceptor-fighter prototype, fitted with a delta vertical tail surface, equipped with a retractable tricycle landing gear, powered by two 980-kg (2,160-lb) thrust M.D.30 (Armstrong Siddeley Viper) turbojet engines; one built.

- Mirage I

- Revised first prototype, fitted with a swept vertical tail surface, powered by two M.D.30R turbojet engines, also fitted with a 1500-kg (3,307-lb) thrust SEPR auxiliary rocket motor.

- Mirage II

- Single-seat delta-wing interceptor-fighter prototype, larger version of the Mirage I, powered by two Turbomeca Gabizo turbojet engines; one built.

- Mirage III-001

- Prototype, powered by a 4490-kg (9,900-lb) thrust Atar 101G2 turbojet engine, also fitted with a SEPR auxiliary rocket motor; one built.

- Mirage IIIA

- Pre-production aircraft, powered by a 6.000 kg (13,228 lb) thrust Atar 9B turbojet engine, also fitted with an auxiliary rocket motor; ten built for the Frence Air Force.

- Mirage IIIB

- Two-seat tandem trainer aircraft, fitted with one piece canopy, also fitted with radio beacon equipment, lacks radar; 59 built for the French Air Force.

- Mirage IIIB-1 : Trials aircraft.

- Mirage IIIB-2(RV) : Inflight refuelling training aircraft.

- Mirage IIIBE : Two-seat training aircraft for the French Air Force, similar to the Mirage IIID; 20 built.

- Mirage IIIBJ : Export version of the Mirage IIIB for Israeli Air Force; five built.

- Mirage IIIBL : Export version of the Mirage IIIB for Lebanese Air Force.

- Mirage IIIBS : Export version of the Mirage IIIB for the Swiss Air Force; four built.

- Mirage IIIBZ : Export version of the Mirage IIIB for the South African Air Force; three built.

- Mirage IIIC

- Single-seat all-weather interceptor-fighter aircraft, equipped with a Cyrano I radar, powered by a 6000-kg (13,228-lb) thrust Atar 9B-3 turbojet engine, fitted with an auxiliary rocket motor in the rear fuselage, armed with two 30-mm cannons, plus one Matra R530 and two AIM-9 Sidewinder air-to-air missiles; 95 built for the French Air Force.

- Mirage IIIC-2 : One aircraft fitted with an Atar 9K-6 turbojet engine.

- Mirage IIICJ : Export version of the Mirage IIIC for the Israeli Air Force; 72 built.

- Mirage IIICS : One evaluation and test aircraft for the Swiss Air Force; one built.

- Mirage IIICZ : Export version of the Mirage IIIC for the South African Air Force; 16 built.

- Mirage IIID

- Two-seat trainer version of the Mirage IIIE.

- Mirage IIID : Two-seat training aircraft for the RAAF. Built under licence in Australia; 16 built.

- Mirage IIIDA : Export version of the Mirage IIID for the Argentine Air Force; four built.

- Mirage IIIDBR : Export version of the Mirage IIID for the Brazilian Air Force; four built.

- Mirage IIIDRR-2 : Refurbished and updated aircraft for the Brazilian Air Force. Two ex-french aircraft sold to brazil in 1988.

- Mirage IIIDE : Export version of the Mirage IIID for the Spanish Air Force; six built.

- Mirage IIIDL : Export version of the Mirage IIID for the Lebanese Air Force; two bult.

- Mirage IIIDP : Export version of the Mirage IIID for the Pakistan Air Force; five built.

- Mirage IIIDS : Export version of the Mirage IIID for the Swiss Air Force; two built.

- Mirage IIIDV : Export version of the Mirage IIID for the Venezuelan Air Force; three built.

- Mirage IIIDZ : Export version of the Mirage IIID for the South African Air Force; three built.

- Mirage IIID2Z : Export version of the Mirage IIID for the South African Air Force, fitted with an Atar 9K-50 turbojet engine; 11 built.

- Mirage IIIE

- Single-seat all-weather fighter-bomber, strike aircraft, powered by an 60.80kN (13,668-lb) thrust Atar 9C-3 turbojet engine, fitted with a Cyrano II radar and a avionics bay behind the cockpit, equipped with a Doppler radar and a TACAN navigation system. 183 built for the French Air Force.

- Mirage IIIEA : Export version of the Mirage IIIE for the Argentine Air Force; 17 built.

- Mirage IIIEBR : Export version of the Mirage IIIE for the Brazilian Air Force; 16 built.

- Mirage IIIEBR-2 : Refurbished and updated aircraft for the Brazilian Air Force. Four ex-French aircraft sold to brazil in 1988.

- Mirage IIIEE : Export version of the Mirage IIIE for the Spanish Air Force; 24 built.

- Mirage IIIEL : Export version of the Mirage IIIE for the Lebanese Air Force; ten built.

- Mirage IIIEP : Export version of the Mirage IIIE for the Pakistan Air Force; 18 built.

- Mirage IIIEV : Export version of the Mirage IIIE for the Venezuelan Air Force; seven built.

- Mirage IIIEZ : Export version of the Mirage IIIE for the South African Air Force; 17 built.

- Mirage IIIO

- Single-seat all-weather fighter-bomber aircraft for the RAAF. Built under licence in Australia; 100 built.

- Mirage IIIR

- Single-seat all-weather reconnaissance aircraft, fitted with five cameras and an infra-red package. 50 built for the French Air Force.

- Mirage IIIRD : Single-seat all-weather reconnaissance aircraft for the French Air Force, equipped with a Doppler navigation radar; 20 built.

- Mirage IIIRJ : Single-seat all-weather econniassance aircraft of the Israeli Air Force. Two Mirage IIICZs converted into reconnaissance aircraft.

- Mirage IIIRP : Export version of the Mirage IIIR for the Pakistan Air Force; 13 built.

- Mirage IIIRS : Exporrt version of the Mirage IIIR for the Swiss Air Force; 18 built.

- Mirage IIIRZ : Export version of the Mirage IIIR for the South African Air Force; four built.

- Mirage IIIR2Z : Export version of the Mirage IIIR for the South African Air Force, fitted with an Atar 9K-50 turbojet engine; four built.

- Mirage IIIS

- Single-seat all-weather interceptor fighter aircraft for the Swiss Air Force, fitted with a Hughes TARAN 18 radar and fire-control system, armed with AIM-4 Falcon and Sidewinder air-to-air missiles. Built under licence in Switzerland; 36 built.

- Mirage IIIT

- One aircraft converted into an engine testbed, it was fitted with a 9000-kg (19,482-lb) SNECMA TF-106 turbofan engine.

- Mirage IIIX

- Proposed version, announced in 1982, fitted with updated avionics and fly-by-wire controls, powered by an Atar 9K-50 turbojet engine. Original designation of the Mirage 3NG.

Derivatives

Mirage 5/Mirage 50

The next major variant, the Mirage 5, grew out of a request to Dassault from the Israeli Air Force. The first Mirage 5 flew on 19 May 1967. It looked much like the Mirage III, except it had a long slender nose that extended the aircraft's length by about half a metre. The Mirage 5 itself led directly to the Israeli Nesher, either through a Mossad (Israeli intelligence) intelligence operation or through covert cooperation with AdA (Armée de l'Air — the French Air Force), depending upon which story is accepted. (See details in the Nesher article.) In either case, the design gave rise to the Kfir, which can be considered a direct descendant of the Mirage III.

Milan

In 1968, Dassault, in cooperation with the Swiss, began work on a Mirage update known as the Milan ("Kite"). The main feature of the Milan was a pair of pop-out foreplanes in the nose, which were referred to as "moustaches". The moustaches were intended to provide better take-off performance and low-speed control for the attack role.

The three initial prototypes were converted from existing Mirage fighters and had non-retractable canards "moustaches". One of these prototypes was nicknamed "Asterix", after the internationally popular French cartoon character, a tough little Gallic warrior with a huge moustache.

A fully equipped prototype rebuilt from a Mirage IIIR flew in May 1970, and was powered by the uprated SNECMA Atar 09K-50 engine, with 70.6 kN (15,900 lbf) afterburning thrust, following the evaluation of an earlier model of this new series on the one-off Mirage IIIC2. The Milan also had updated avionics, including a laser designator and rangefinder in the nose. A second fully equipped prototype was produced for Swiss evaluation as the Milan S.

The canards did provide significant handling benefits, but they had drawbacks. They blocked the pilot's forward view to an extent, and set up turbulence in the engine intakes. The Milan concept was abandoned in 1972, while work continued on achieving the same goals with canards.

Mirage 3NG

Following the development of the Mirage 50, Dassault had experimented with yet another derivative of the original Mirage series, named the Mirage 3NG (Nouvelle Génération, next generation). Like the Milan and Mirage 50, the 3NG was powered by the Atar 9K-50 engine. The prototype, a conversion of a Mirage IIIR, flew in December 1982.

The 3NG had a modified delta wing with leading-edge root extensions, plus a pair of fixed canards fitted above and behind the air intakes. The canards provided a degree of turbulent airflow over the wing to make the aircraft more unstable and so more maneuverable.

Avionics were completely modernized, leveraging off the development effort for the next-generation Mirage 2000 fighter. The Mirage 3NG used a fly-by-wire system to allow control over the aircraft's instabilities, and featured an advanced nav/attack system; new multimode radar; and a laser rangefinder system. The uprated engine and aerodynamics gave the Mirage 3NG impressive performance. The type never went into production, but to an extent the 3NG was a demonstrator for various technologies that could be and were featured in upgrades to existing Mirage IIIs and Mirage Vs.

After 1989, enhancements derived from the 3NG were incorporated into Brazilian Mirage IIIEs, as well as into four ex-Armée de l'Air Mirage IIIEs that were transferred to Brazil in 1988. In 1989, Dassault offered a similar upgrade refit of ex-AdA Mirage IIIEs under the designation Mirage IIIEX, featuring canards, a fixed in-flight refueling probe, a longer nose, new avionics, and other refinements.

A total of 1,422 Mirage III/5/50 aircraft of all types were built by Dassault. There were a few unbuilt variants:

- A Mirage IIIK that was powered by a Rolls-Royce Spey turbofan was offered to the British Royal Air Force.

- The Mirage IIIM was a carrier-based variant, with catapult spool and arresting hook, for operation with the French Aéronavale.

- The Mirage IIIW was a lightweight fighter version, proposed for a US competition, with Dassault partnered with Boeing. The aircraft would have been produced by Boeing, but it lost to the Northrop F-5 Freedom Fighter.

Balzac / Mirage IIIV

One of the offshoots of the Mirage III/5/50 fighter family tree was the Mirage IIIV vertical take-off and landing (VTOL) fighter. ("IIIV" is read "three-vee," not "three-five"). This aircraft featured eight small vertical lift jets straddling the main engine. The Mirage IIIV was built in response to a mid-1960s NATO specification for a VTOL strike fighter.

Mirage III ROSE

Project ROSE (Retrofit Of Strike Element) was an upgrade programme launched by the Pakistan Air Force to upgrade old Dassault Mirage III and Mirage 5 aircraft with modern avionics. In the early 1990s the PAF procured 50 ex-Australian Mirage III fighters, 33 of which were selected after an inspection to undergo upgrades. In the first phases of Project ROSE the ex-Australian Mirage III fighters were fitted with new defensive systems and cockpits, which included new HUDs, MFDs, RWRs, HOTAS controls, radar altimeters and navigation/attack systems. They were also fitted with the FIAR Grifo M3 multi-mode radar and designated ROSE I. Around 34 Mirage 5 attack fighters also underwent upgrades designated ROSE II and ROSE III before Project ROSE was cancelled. The Mirage III/5 ROSE fighters are expected to remain in service with the PAF until replacement in the mid-2010s.

Operators

Abu Dhabi (retired)

Abu Dhabi (retired) Argentina

Argentina Australia (retired 1988, 50 sold to Pakistan)

Australia (retired 1988, 50 sold to Pakistan).svg.png) Belgium (retired)

Belgium (retired) Brazil (retired 2005)

Brazil (retired 2005) Chile (retired)

Chile (retired) Colombia

Colombia Egypt (retired)

Egypt (retired) France (retired)

France (retired) Gabon

Gabon Israel (retired)

Israel (retired) Lebanon (sold to Pakistan in 2000)

Lebanon (sold to Pakistan in 2000) Libya

Libya Pakistan

Pakistan Peru (retired)

Peru (retired) South Africa

South Africa Spain (retired in 1991, sold to Pakistan in 1992)

Spain (retired in 1991, sold to Pakistan in 1992) Switzerland (retired)

Switzerland (retired) Venezuela

Venezuela Zaire

Zaire

Specifications (Mirage IIIE)

General characteristics

- Crew: 1

- Length: 15 m (49 ft 3.5 in)

- Wingspan: 8.22 m (26 ft 11 in)

- Height: 4.5 m (14 ft 9 in)

- Wing area: 34.85 m² (375 ft²)

- Empty weight: 7,050 kg (15,600 lb)

- Max takeoff weight: 13,500 kg (29,700 lb)

- Powerplant: 1× SNECMA Atar 09C turbojet

Performance

- Maximum speed: Mach 2.2 (2,350 km/h, 1,460 mph)

- Range: 2,400 km (1,300 NM, 1,500 mi)

- Service ceiling: 17,000 m (56,000 ft)

- Rate of climb: 83.3 m/s (16,400 ft/min)

- Wing loading: 387 kg/m² (79 lb/ft²)

Armament

- Guns: 2× 30 mm (1.18 in) DEFA 552 cannons with 125 rounds per gun

- Rockets: 2× Matra JL-100 drop tank/rocket pack, each with 19× SNEB 68 mm rockets and 66 US gallons (250 liters) of fuel

- Missiles: 2× AIM-9 Sidewinders OR Matra R550 Magics plus 1× Matra R530, 2× AM-39 Exocet anti-ship missiles

- Bombs: 4,000 kg (8,800 lb) of payload on five external hardpoints, including a variety of bombs, reconnaissance pods or Drop tanks; French Air Force IIIEs through 1991, equipped for AN-52 nuclear bomb).

Mirage III C |

Mirage III E |

Notable appearances in media

The Mirage fighter aircraft series is featured in the popular French comic Tanguy et Laverdure. The stories were made into the 1967–1969 French TV series Les Chevaliers du Ciel, and a French feature film Les Chevaliers du ciel (international title Skyfighters) in 2005, in which the Mirage 2000 is flown instead.

See also

Related development

- Atlas Cheetah

- Dassault Mirage IV

- Dassault Mirage 5

- Dassault Mirage IIIV

- Dassault Mirage 2000

Comparable aircraft

- Chengdu J-7

- Convair F-102 Delta Dagger

- Convair F-106 Delta Dart

- English Electric Lightning

- Lockheed F-104 Starfighter

- Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-21

- Saab 35 Draken

- Sukhoi Su-9

- Sukhoi Su-11

Related lists

- List of Dassault Mirage III operators

- List of fighter aircraft

- List of military aircraft of France

References

- Notes

- ↑ Swiss Air Force. "Aircraft". http://www.lw.admin.ch/internet/luftwaffe/en/home/dokumentation/assets/aircraft/historical.html. Retrieved 9 April 2010.

- Bibliography

- Atlejees, Leephy. Armscor Film by Armscor, SABC and Leephy Atlejees. Public broadcast by SABC Television, 1972, rebroadcast: 1982, 1984.

- Baker, Nigel and Tom Cooper. "Middle East Database: Dassault Mirage III & Mirage 5/Nesher in Israeli Service".www.acig.org, Air Combat Information Group Journal (ACIG), 26 September 2003. Retrieved: 1 March 2009.

- Breffort, Dominique and Andre Jouineau. "The Mirage III, 5, 50 and derivatives from 1955 to 2000." Planes and Pilots 6. Paris: Histoire et Collections, 2004. ISBN 2-913903-92-4.

- "Cheetah: Fighter Technologies". Archimedes 12. June 1987.

- Cooper, Tom. "Middle East Database: War of Attrition, 1969-1970." www.acig.org, Air Combat Information Group Journal (ACIG), 24 September 2003. Retrieved: 1 March 2009.

- "The Designer of the B-1 Bomber's Airframe". Wings Magazine, Vol. 30/No 4, August 2000, p. 48.

- Donald, David and Jon Lake, eds. Encyclopedia of World Military Aircraft. London: AIRtime Publishing, 2000. ISBN 1-880588-24-2.

- Green, William and Gordon Swanborough. The Complete Book of Fighters. New York: Smithmark Books, 1994, ISBN 0-07607-0904-1.

- Jackson, Paul. "Mirage III/5/50 Variant Briefing". World Air Power Journal 14, 15, 16.

- Lake, Jon. "Atlas Cheetah". World Air Power Journal 27: 42–53, Winter 1966.

- Pérez, San Emeterio Carlos. Mirage: Espejismo de la técnica y de la política. Madrid: Armas 30. Editorial San Martin, 1978. ISBN 8-47140-158-4.

- Rogers, Mike. VTOL Military Research Aircraft. London: Foulis, 1989. ISBN 0-85429-675-1.

- Schürmann, Roman. Helvetische Jäger. Dramen und Skandale am Militärhimmel (in German). Zürich: Rotpunktverlag, 2009. ISBN 978-3-85869-406-5.

The initial version of this article was based on a public domain article from Greg Goebel's Vectorsite.

External links

- The History of the Dassault Mirage III in Brazil (with pictures) - Milavia.net

- The Dassault Mirage III/5/50 Series from Greg Goebel's AIR VECTORS

- Mirage III/5/50 at FAS.org

- Mirage Argentina, el sitio de los Deltas argentinos - details, side views, and pictures of Argentine mirages (in Spanish). Retrieved: 17 May 2008,

Official Page of the swiss Air Foorce in German (more details as in the english version)

|

|||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||